The Next Fire Is Already Smoldering: What Washington, D.C. Is Willfully Ignoring in Ferry County

“It was moving pretty fast. I could see the flames and was like, ‘I think we’re going down.’”

—Gina Lawrence, Colville tribal member, recalling her evacuation during the 2020 Cold Springs Fire (High Country News, May 2025)

Gina Lawrence didn’t wait for the official warning. As flames from the Cold Springs Fire bore down on her home in 2020, she packed what she could and ran. That moment, a terror stripped of time, has not left her. Nor has the realization that her community, like so many across the Colville Reservation and Ferry County, is often left to face wildfire season with little more than courage and outdated radios.

Four Years Later, The Fear Has Returned

In July 2024, the Swawilla Fire consumed over 53,000 acres across tribal and non-tribal lands in Ferry County. Smoke blanketed Buffalo Lake. The Keller Ferry was shut down. Evacuation orders covered broad swaths of land. And already this year, in April 2025, the Stray Dog Fire ignited near Inchelium, underscoring what residents already knew: fire season is longer, hotter, and crueler now. According to Headwaters Economics, more than 12,000 properties in Ferry County face moderate to high wildfire risk. In a county where most firefighting is handled by volunteers, the system is buckling under that pressure.

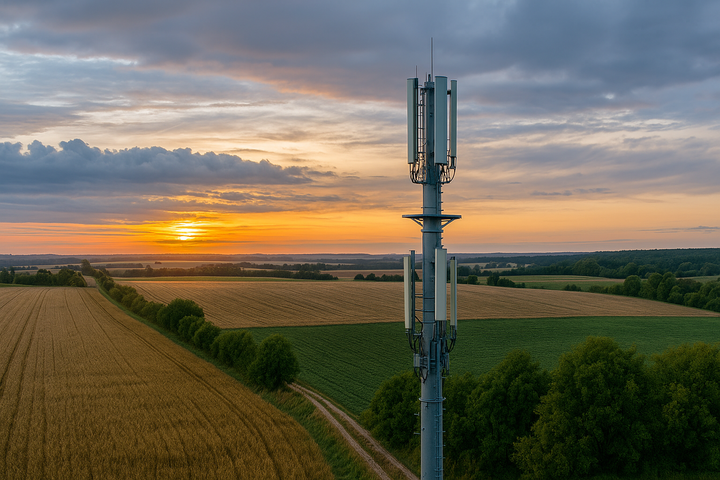

Even as fires burn faster, help keeps stretching thinner. Ferry County has long used E‑911, but it has yet to adopt the new NextGen technology being rolled out statewide, which would allow for more resilient and interoperable communication during emergencies. Observers report persistent radio dead zones in the county’s more remote terrain. And while the Mt. Tolman Fire Center’s tribal crews continue to serve as indispensable first responders, there is no public record of recent federal investment in upgrading their dispatch or coordination systems. What little outside support they did have was quietly cut in Washington this spring.

Neglect by Design

After years of underfunding, and with no consistent federal investment in tribal coordination or rural dispatch infrastructure, the cracks in the system have widened into chasms. When help does not arrive, it is not a logistical oversight. It is the product of a long pattern of deliberate neglect.

“Everybody’s so spread out that we don’t have anybody to come,” a Colville tribal firefighter told High Country News in 2025.

Rural fire services across eastern Washington, especially in Ferry County, haven’t just been overlooked. They’ve been left behind. Washington, D.C. has turned its back on the infrastructure and personnel that protect these communities. And now, their own congressional representative has joined that neglect, turning his back on the firefighters, volunteers, and rural families he was elected to defend.

On May 22, 2025, just a month after the Stray Dog Fire, WA-5 Rep. Michael Baumgartner voted for the so-called "One Big, Beautiful Bill", a sweeping federal package that delivered what his office called a “major win for taxpayers.” For Ferry County, it read more like a withdrawal notice from Washington, D.C.

Among the cuts were core programs that rural emergency response depends on:

- Federal support for 911 system upgrades and emergency communications

- Clean energy and rural fire prevention grants

- U.S. Forest Service and Interior Department staff positions tied to fire coordination

- Air-quality monitoring tools used during wildfire smoke events

- Funds for renewable fuels and backup power systems

While Baumgartner’s press release praised the bill’s tax cuts. It did not mention wildfire. It did not mention emergency response. And it did not mention the rural communities in his own district already living in the shadow of fire.

It was a stunning act of legislative neglect.

It also wasn’t his first. Baumgartner remained silent on Initiative 2117, which sought to repeal Washington’s Climate Commitment Act, a law that has already steered over $83 million toward wildfire resilience programs statewide. Ferry County has yet to see meaningful benefit from those funds. And there's no record of Baumgartner requesting any.

Meanwhile, another deadline looms.

A Test of Will at Home

On June 16, 2025, Ferry County residents will gather for a Public Utility District (PUD) rate hearing in Republic. It’s the first proposed rate hike since 2017. But the draft budget does not include a single line item for wildfire prevention, emergency radios, or evacuation infrastructure. Residents will be asked to pay more, but still be left to fend for themselves.

The symbolism is sharp. Even as federal lawmakers gut rural emergency preparedness, local institutions are left with impossible choices. As fire risk expands, budgets remain static. As volunteers hold the line, elected officials offer lip service. And as communities like Keller, Inchelium, and Curlew brace for another season of heat and smoke, they do so knowing the systems meant to protect them are running on fumes.

Ferry County’s Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP) hasn’t seen a comprehensive update since 2019. No new brush-clearing grants. No tribal coordination dollars. No satellite communications. All of this, even as the First Street Foundation warns that 98% of the county’s properties will face some level of wildfire risk in the coming decades.

The numbers are terrifying. But the silence from Congress is worse.

Wildfire policy isn’t abstract. It’s the difference between a warning and a tragedy. It’s road signs that don’t melt, school HVAC systems that filter smoke, and radios that work when the winds shift. It’s part-time fire chiefs sleeping in trucks, praying the flames don’t turn. It’s Gina Lawrence, throwing clothes in her car, not knowing if her house will still be there. And it’s a question Rep. Baumgartner still hasn’t answered:

Why, when Ferry County needed federal support the most, did he cast a vote that pulled the plug on the very systems meant to protect his constituents?

Sources