This Land Is Us: A Rural County Fought Back Against Washington, D.C. and Won

Where Neighbors Still Show Up

At the Republic Library on a weekday morning, someone is always stopping by. A teacher drops off flyers for the summer reading program. A teenager scrolls through job listings on the public Wi-Fi. Children gather around bins of Legos and puzzles while quiet conversation drifts from the community room. Flyers for trail days and library fundraisers crowd the bulletin board, including one for the Stonerose Fossil Center’s family dig program.

In Ferry County, the Republic Library on Clark Avenue is more than a place to check out books. It’s a meeting space, a tech support center, a learning hub, and one of the few indoor places where neighbors still gather without an agenda. “Rural libraries are hubs of community services that go well beyond what people understand a normal library to be,” said Emily Burt, co-chair of the library’s Friends board, after the building became a flashpoint in a recent free speech fight.

This Place Runs on People and Public Land

A few blocks down the street, the lights are on at Republic Brewing Company. Billy and Emily Burt run the place out of the old fire station, serving beer made with mountain water. The same Emily who defended the library also helps host open mic nights, sponsor trail cleanups, and organize Get Out Fest every summer. On weekends, they’re out skiing or hiking the same national forest that surrounds the town and much of the county.

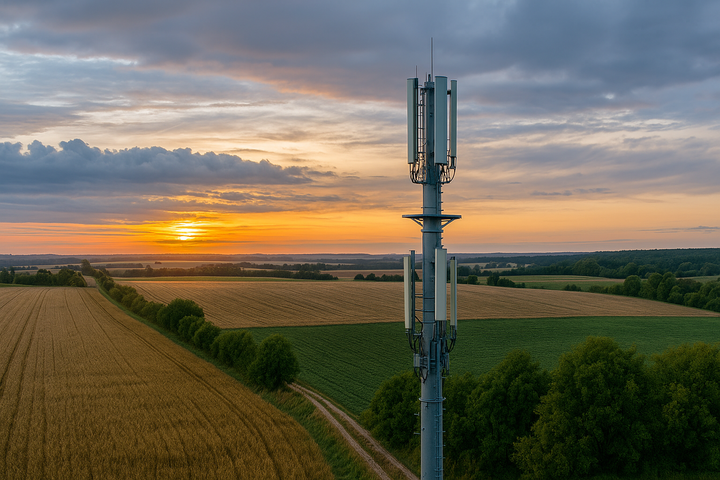

Ferry County is easy to overlook. It’s small. Remote. Many of its small towns are marked by weathered storefronts and historic buildings that make a traveler want to linger and explore. But it is deeply rooted in the public land it depends on. Trails, hunting grounds, fishing holes, and firewood permits aren’t extras here. They are the infrastructure of rural life. And until very recently, they were at risk.

What They Tried to Take

Buried inside a sweeping federal budget proposal in Washington, D.C., nearly 2,500 miles and worlds apart from Republic, was a provision that would have allowed the sale of large portions of public land across eleven western states. Much of that land sits inside counties like Ferry, where the federal government owns most of the acreage and the limited private land barely generates enough tax revenue to sustain local services. The justification was budget efficiency. But the real impact would have been the transfer of access, ownership, and stewardship from the public to private timber and mining interests.

How Small Places Pushed Back

Ferry County wasn’t alone in pushing back. Across the West, small towns began spreading the word. In local Facebook groups, community forums, and county commission meetings, people spoke up. They didn’t make national headlines. They didn’t charter buses to Washington, D.C. But together, these rural communities formed a quiet chorus. And the message they sent was clear.

Here, the land is not for sale.

Who Didn’t Speak Up

In Ferry County, that message passed from neighbor to neighbor. A call to action circulated online: “Take a few minutes to fill this simple form out if you oppose the sale of public lands.” It wasn’t dramatic. It didn’t need to be. The groundswell of opposition, spanning all eleven affected western states, sparked a bipartisan effort in the halls of Congress to strip the land sale amendment from the budget. But not everyone with power stepped up. Washington’s entire congressional delegation, including Ferry County’s own Representative Michael Baumgartner, remained publicly silent. Weeks later, the provision was quietly removed from the final version of the bill.

The Win That Proved We Still Matter

Victory didn’t belong to any one place. But for counties like Ferry, it was proof of something often forgotten: small rural communities still have power. Not because they shout the loudest, but because they know what’s at stake.

You can feel that stake in the rhythms of everyday life. At the Republic Library, where a laminated trail map hangs near the bulletin board, and where more than one conversation begins with the question, “You headed up past Sherman Pass this weekend?” Or at the brewery, where people linger after live music or a poetry night, talking about snowpack, timber sales, and trail conditions. These aren’t abstract debates about public policy. They are conversations about home.

What It Means to Belong

This story isn’t about a dramatic fight between David and Goliath. It’s about a rural county that understood what it stood to lose, and quietly refused to let it happen. A simple place, trying to stay whole, that recognized a threat, spoke up, and helped stop something that never should have been proposed in the first place.

The library is still open. The trails are still public. And the people of Ferry County are still here, watching, speaking, showing what it means to belong to a place, and to one another.